by Lorena Llevado Sellers

When I think about the journey that I and so many of my “kababayans” make in our lives, it is really amazing. Today I live in California and take advantage of all the technology there is in the world today to stay in touch with my family in the Philppines — we talk on the phone every day, we are on sites like FaceBook–we are all able to stay connected and the technology let’s us do that. Growing up as I did, i could never have, even in my wildest possible dreams, imagined where life’s journey has taken me. But I want to make sure that I never forget where the journey started, and how I grew up in a world so different from the one I am part of today…..

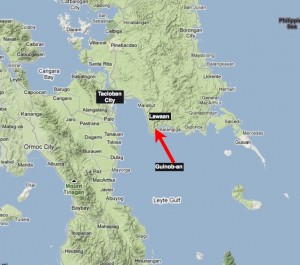

My full name given to me by my parents is Lorena Bohol Llevado, and I was born without any help from a doctor in the house that my parents Loreto and Tarcila shared with my mom’s mother, Sylvestra, on September 20, 1974. Our town is Guinob-an, a barangay of the municipality of Lawaan in the Eastern Samar, Philippines. Eastern Samar is part of the Visayas, the central part of the Philippines. The nearest city was Tacloban, the capital of Leyte, our neighbor province, which was a two hour boat ride away.

Waray People — and “Waray Na”

We are Waray — famous in the Philippines as being maybe the fiercest warriors — we were the ones who attacked and overwhelmed the Americans in Balangiga (our neighboring town) in 1901 and we celebrate the Balangiga Encounter every year with a holiday, a re-eenactment, and celebrations. We are “Waray”, and we say “waray” in the same way that in Tagalog you say “wala” — meaning, “there is nothing”. What does it mean that the name of our people is the same as the word for having nothing? Maybe it’s a good thing that we are humble, but tough…(Michael found a pretty good discussion of the possible meaning of “Waray” — here is the link.)

Guinob-an

Guinob-an is a seaside barrio of the municpality of Lawaan. When I was born Guinob-an had about 100 families living beneath coconut trees on a narrow strip of land between the Leyte Gulf and jungle covered hills on the inland side. Our houses were raised about 4 feet off the ground and made of wood and plaster, with corrugated tin or thatched roofs. There was no road in or out of the town, you could only reach it by water and by footpaths until a coastal road was completed in the 1990’s. There was no electricity, no running water, no TV, no ice, no real contact with the outside world.

Guinob-an is a seaside barrio of the municpality of Lawaan. When I was born Guinob-an had about 100 families living beneath coconut trees on a narrow strip of land between the Leyte Gulf and jungle covered hills on the inland side. Our houses were raised about 4 feet off the ground and made of wood and plaster, with corrugated tin or thatched roofs. There was no road in or out of the town, you could only reach it by water and by footpaths until a coastal road was completed in the 1990’s. There was no electricity, no running water, no TV, no ice, no real contact with the outside world.

Life in Guinob-an in the 1970’s was probably very much the way it had been for centuries. Water came from a well in the town square, and a stream that brought clear water down from the jungle . There was a two room school, an outdoor basketball court that was also our town plaza, and a small building near the plaza that served as a part-time clinic operated now and then by visiting government doctors.

There were no vehicles in the town; every family had at least one home-made “binigiw”, a stype of native constructed “baloto” — fishing boat carved from a tree trunk with bamboo sides which we would make waterproof with tree sap.

There was very little money in Guinob-an, and not too much need for it. Families lived by catching fish and growing crops in nearby farm plots, mostly for family use — using most of the fish and vegetables for themselves, but selling some of it to other families to get a small amount of cash for the few cash purchases that were necessary — rice, oil, sugar, salt, kerosene, batteries — most of which could be purchased from one of several tiny “sari-sari” stores attached to a few of the houses in the village. Shorts, flip-flops, t-shirts, simple dresses, and school uniforms could be purchased at the dry market in Lawaan. Many of the families had farm plots in the hills where coconut trees grew and, underneath the coconut trees, other crops were planted in the cleared soil of the coconut groves. The coconuts provided the main source of cash from crops.

For us, the coconut really was very important. It provided everything from construction materials to cooking oil (my mother would make coconut cooking oil at home to avoid having to pay cash to buy oil from the sari sari store). I remember grinding coconut meat using a “kaguran” and, because I was too light to hold it steady, I had to have another sister sit behind me and hold her down. You sit on the stool and use your weight to hold the grinder steady, then take the coconut halves and scrub them on the grinder ball.

For us, the coconut really was very important. It provided everything from construction materials to cooking oil (my mother would make coconut cooking oil at home to avoid having to pay cash to buy oil from the sari sari store). I remember grinding coconut meat using a “kaguran” and, because I was too light to hold it steady, I had to have another sister sit behind me and hold her down. You sit on the stool and use your weight to hold the grinder steady, then take the coconut halves and scrub them on the grinder ball.

I also remember that during the coconut harvest at the family plot, I would dig among the piles of coconuts searching for overripe ones that had started to sprout, knowing that these contained a sweet and tasty “buwa” — which I have a hard time describing so here is a picture of one. (Michael Note: It’s officially described as a “fleshy, germinating breadlike bulb growing in the interior of the coconut. ) (see picture of a “buwa” to the right)

Mostly — everyone lived by fishing, tending crops, and selling just enough here and there to make money for the few necessities that had to be bought. But there were also several family owned copra processing operations where coconut husks were dried and copra produced. There was also an on-again, off-again project to build a coastal road which began as a dirt track completed when I was in high school, and which finally became a paved road in 2000. The road project from time to time provided jobs for the young men of Guinob-an — but nothing regular. It was strictly a hit or miss project which was inactive more than it was active.

Overall Guinob-an was a poor community — but I didn’t really think of it that way. Even when we didn’t have enough food — which happened not a lot, but wasn’t really rare — I guess I just didn’t understand that there was any other way to live. Besides — we were right beside the beautiful Leyte Gulf, there were coconut trees everywhere, a guava trees, and the climate was tropical so we didn’t have great need for clothes, shoes, heating, and shelter.

My father Loreto was a lean, very strong man of forty when I was born. Now he is in his seventies (pictured below left). He is still very thin and has a lean, strong body. Like most of the men in Guinob-an, he was a fisherman when the fishing was good. During the months of March to May he and the others would paddle out in his one man “binigiw” outrigger canoe (or sail out if the wind was favorable) to fish for marlin and sailfish which were plentiful just a few miles offshore and could be caught on handlines using baits tied to floating drums. He would put out half a dozen baits and watch them. A strike would cause the floating drum to disappear under water briefly , and then he would chase it down using paddle and sail, throw a line around it, and begin working the fish. Upon catching a single marlin or sailfish, he would lash the fish to the side of the boat and paddle home.

My father Loreto was a lean, very strong man of forty when I was born. Now he is in his seventies (pictured below left). He is still very thin and has a lean, strong body. Like most of the men in Guinob-an, he was a fisherman when the fishing was good. During the months of March to May he and the others would paddle out in his one man “binigiw” outrigger canoe (or sail out if the wind was favorable) to fish for marlin and sailfish which were plentiful just a few miles offshore and could be caught on handlines using baits tied to floating drums. He would put out half a dozen baits and watch them. A strike would cause the floating drum to disappear under water briefly , and then he would chase it down using paddle and sail, throw a line around it, and begin working the fish. Upon catching a single marlin or sailfish, he would lash the fish to the side of the boat and paddle home.

Other times of the year he fished for Lapu-lapu, grouper, and other bottom fish. My mother is Tarcila, also in her early 70’s now — and she raised not only her own 12 chidren, but half a dozen grandchildren, and held our family together through economic and natural catastrophes. She’s lived a hard life but still has a quick and hearty laugh.

Life at Home

There are no pictures of me from my childhood — cameras weren’t part of our world. I imagine I looked a lot like my nieces in the picture to the left — at least in my imagination. By the time I was 4, many of my older siblings had grown up and left home. My dad Loreto and one brother, Ronnie, would paddle out at 2 in the morning to fish, then paddle or sail back late in the afternoon around 2 or 3 pm. My Dad would carry with him a small “baon” pot of rice and some vegetables, sometimes some grilled fish or other toppings as well if they were available — and when he would home I would always race down to the waterfront and jump into the boat, looking for leftover “baon”. Almost always there would be some. My Dad never ate everything, he always left something for me except a few times when he got caught in rough weather and couldn’t use the sail, and had to paddle all the way out and all the way back. On thoese days he needed all the rice for “fuel” — and I understood.

There are no pictures of me from my childhood — cameras weren’t part of our world. I imagine I looked a lot like my nieces in the picture to the left — at least in my imagination. By the time I was 4, many of my older siblings had grown up and left home. My dad Loreto and one brother, Ronnie, would paddle out at 2 in the morning to fish, then paddle or sail back late in the afternoon around 2 or 3 pm. My Dad would carry with him a small “baon” pot of rice and some vegetables, sometimes some grilled fish or other toppings as well if they were available — and when he would home I would always race down to the waterfront and jump into the boat, looking for leftover “baon”. Almost always there would be some. My Dad never ate everything, he always left something for me except a few times when he got caught in rough weather and couldn’t use the sail, and had to paddle all the way out and all the way back. On thoese days he needed all the rice for “fuel” — and I understood.

Our family house was actually the house of my mom’s mother Silvestra–my ‘inay’ — and was the house where my mom had grown up. It was a small, square — maybe 600 square feet altogether made of wooden frame and corrugated tin, on wood posts 4 feet above the ground. There was a bedroom where I slept on a grass mat with the other children, and a “sala” which was our living room and where, at the end of the day, the parents and ‘inay’ would pull out sleeping mats and sleep on the floor with whatever other kids or grandchildren were there and who couldn’t fit in the room with me. In the sala there were two benches beside the windows, which were wooden flaps with a pole to prop them open –otherwise there were no furnishings inside the sala, which made sense because we had to keep the floor clear for sleeping at night. There were kerosene lamps at the end of the benches — these were the only lights in the house.

Our family house was actually the house of my mom’s mother Silvestra–my ‘inay’ — and was the house where my mom had grown up. It was a small, square — maybe 600 square feet altogether made of wooden frame and corrugated tin, on wood posts 4 feet above the ground. There was a bedroom where I slept on a grass mat with the other children, and a “sala” which was our living room and where, at the end of the day, the parents and ‘inay’ would pull out sleeping mats and sleep on the floor with whatever other kids or grandchildren were there and who couldn’t fit in the room with me. In the sala there were two benches beside the windows, which were wooden flaps with a pole to prop them open –otherwise there were no furnishings inside the sala, which made sense because we had to keep the floor clear for sleeping at night. There were kerosene lamps at the end of the benches — these were the only lights in the house.

My mom cooked on an open fire in the yard by the back porch where there was a small pantry/dining area with a long dining table, big enough so that 12 could eat together. This table was the main place where people would “hang out” — not the sala.

We didn’t have inside plumbing or running water; no electricity; no TV — but then nobody else in my world had those things either so I didn’t realize we were missing anything. Our only link with the “outside world” was a battery powered radio my Dad used, mainly to get weather reports that would let him know when it was safe to go fishing. The radio wasn’t used for general listening — because batteries cost money–except for a occasional radio soap opera that the whole family would gather and listen to.

I was the youngest of 12 kids but some of them were already gone by the time I came along — and there were a few grandchildren living in the house. I was the youngest of the “originals”, and kind of the “eldest” of the second wave — the grandchildren, and was like an “ate” (older sister) to them. Living in our house when I was small were my “inay” Sylvestra, my Dad Loreto, my mom Tarcila (except for a two year stretch when I was very young and my mom went to Manila), my sister Eva (8 years older than me, my brother Rommel (two years older than me), sister Rowena (5 years older than me), sister Lisa (4 years older than me), and two grandchildren who were younger than I was — Eileen (7 years younger than Rena), and Yolanda (6 years younger than Rena). In an odd way, in spite of being the “baby” of the original 12 kids,

During the daytime the “bathroom” was the surrounding bushes and jungle; at night there was a hole in the floor at a corner of the house which could be used although the adults would generally go outside at night too.

Most days we would go to be shortly after sunset and get up right around dawn. But one of my most vivid memories is how, on the nights when there was a full moon, the family would not go to bed shortly after dusk but would, along with other villagers, stay outside, the parents talking and the kids playing in the bright tropical moonlight.

Two Near Tragedies

There were two near tragedies in my early life. The first occurred when I became very ill as a baby and my parents (who had lost two other babies to disease) became convinced I was going to die. Being Catholic they offered prayers and promises of penitence if I could only live, which I did (obviously!). To make good on the promise of penitence, my parents still make a trip every year to a special church in Sulangan, near Guiuan, on the southern tip of Eastern Samar, where they give thanks and sponsor a mass.

This is an annual family tradition that continues to this day.

The second near tragedy occurred on Christmas Eve, 1975, when I was 15 months old. My mother was in Manila at the time, and “inay” (grandmother) Silvestra was in charge of the house, but was out in the yard cooking the Noche Buena meal that would be served at midnight. My elder sister Eva, who was then about 12, was caring for me and myr sister Lisa, who was 6 or 7. (I was too young to remember any of this, but I’ve been told the story so many times that it almost seems like I can remember it.)

“Inay” asked Eva to give me a bath and put me to bed. I was on one of the benches in the sala — the ones with the kerosene lantern on the end. She brought out a big pot filled with warm water and gave me a bath — no problem with that. But then I evidently wanted to sleep in a special dress– one that had a picture of a cat on it. Eva tried to convince me to leave the dress for tomorrow, Christmas Day, but I wasn’t having any of it and so Eva went off to fetch the dress. She returned and didn’t notice that while she had been gone, I had moved closer to the kerosene lamp at the end of the bench. Eva then began wrestling me into the dress. Lisa, on a sleeping mat on the floor next to the bench, was rocking herself to sleep, sucking on her thumb as she always did. Eva would later tell everyone that the first sign of trouble came when sheheard Lisa on the floor making some strange sounds but Lisa had her thumb in her mouth the sounds didn’t really register with Eva, who had no idea what was happening until she looked up and realized that the front of my dress (made of very flammable nylon–forget about fireproof clothing in those days) was in flames. I hadn’t started screaming yet because the flames hadn’t reached my body. Eva quickly put out the fire but not before the flames and melted nylon reached my stomach, creating a seriously horrid third degree burn in which the nylon materials melted into my burned flesh.

Once I was burned, of course I started screaming — loud enough for the neighbors to come running. The first to arrive was my uncle, Pablito, who lived next door. Pablito was immediately angry with Eva for letting such a thing happen–so much so that he grabbed a stick and made “palo” (i.e. he whacked her with it), all the while trying to calm me as he angrily asked my very scared sister Eva what was she thinking — was she trying to make Christmas “lechon” (roasted pig) out of the baby?

There was no thought of taking me to a hospital. No money, no hospital–it just wasn’t part of our world. Instead, my inay prepared an herbal mixture and washed the wound with warm water and herbs, and then she poured powdered penicillin purchased at the local sari-sari store directly into the wound. This, plus cutting holes in the front of my dresses where the wound was healing, was the only treatment.

Painful days and weeks passed but the penicillin kept infection at bay and the wound eventually began to heal. Today I still have a four inch scar which you can clearly see in bright light (not so much in dim light)–a scar that just visible enough to prompt a question or two but isn’t really ugly or anything. I’ve thought about trying to have it made completely invisible but on I think I prefer to keep it as a reminder of things past. I’ve often thought about how painful that burn must have been, and how living with that pain for weeks and quite probably months as a young child must have had an effect on me — but I can’t rally remember the experience so I just don’t know.

(to be continued)……