In the Philippines, a 14 year period of Martial Law began in 1972, and I was born in 1974, so I grew up under Martial Law until I was 12. There was great tension between the mililtary and the communist NPA rebels who opposed them, and this ended up affecting our lives in some very frightening and important ways. But in my earliest childhood I was only vaguely aware that the military was in charge of things — other than that, it didn’t mean a lot. That would come later.

HOW WE LIVED THEN

Our basic way of living relied on nature, not cash — or at least not much cash. For food there was the fish caught by my father, plus vegetables and root crops grown in a small “farm” that was a 45 minute walk up into the jungle hillside into the forest. This left only rice, oil, sugar, kerosene, and salt as items that needed to be bought with with cash on a regular basis. Water came from a well and a stream. There was no such thing as a mortgage to be paid — the house was owned outright; there were no utility bills because there were no utilities–no running water, no electricity, none of that. We cooked using a woodfire and, later when I was in high school, we learned how to make charcoal. Lighting was provided by kerosene lamps, which was a problem when times were bad–which was often–and so the we ate dinner around sunset and would go to bed shortly after dusk.

THE FAMILY “FARM”

Some days my mom would cook something to sell, or mend clothes for the children or grandchildren. One time she made a dress from scratch for me, using leftover materials and patching them together. Occasionally she would play cards with friends. I would stay with her most of the time, until I started going to school. I especially remember the times we would go to our farm–it seemed like at least two or three days a week would be spent there, managing the crops which provided much of the food we ate–sometimes all of it.

Some days my mom would cook something to sell, or mend clothes for the children or grandchildren. One time she made a dress from scratch for me, using leftover materials and patching them together. Occasionally she would play cards with friends. I would stay with her most of the time, until I started going to school. I especially remember the times we would go to our farm–it seemed like at least two or three days a week would be spent there, managing the crops which provided much of the food we ate–sometimes all of it.

Having a jungle farm was normal in Guinob-an. The town is right on the Leyte Gulf, but there are forested jungle hills that come right down to the edge of the town. Most families had a plot of land somewhere up in the jungle — our “farm” was a slippery, uphill, 45 minute walk from home on jungle trails which ended at a clearing that had half a hectare of coconut trees with cleared land underneath where we planted other crops. It was on on property that the family inherited from my mom’s mother. It had a tiny nipa hut — just a basic bit of shade to rest in after lunch — with coconut trees everywhere and, beneath them, banana and papaya, and root crops of sweet potato, cassava, ube (a purple sweet potato), another root crop called “gaway”, plus vegetables — okra, string beans, squash, ampalaya greens, sugar cane.

The sugar cane was my favorite– as a kid I would make the long, muddy walk up to the farm with my mom and, as soon as we got there, I would grab a piece of sugar cane, then climb our guava tree and sit ther for hours, swinging the guava tree and munching on sugar cane and guava while my mom worked below.

At the farm I also learned to climb coconut trees, and as I grew older it became apparent that I was a bit of a tomboy who could keep up with the boys at any game. (Michael Comment: When I first met her Rena was just turning 21 and at some point she told me about her coconut tree climbing prowess. I asked her if she could climb one of the trees at the beach where we used to go near Subic … she answered very seriously that she wasn’t sure, it had been a long time — she hadn’t climbed one in “at least a year of two.” For me, thinking that a year earlier she was climbing cocount trees in distant Samar was in some way astonishing. )

Although we didn’t need a lot of cash — we did need some, and the only way we could get any cash at all was to sell fish vegetables, or cooked food, to villagers who were better off financially than we were. My “department” was fish sales. When my Dad (who fished traditionally with a handline and hook) or brother Ronnie (who was a spearfisherman) brought home the catch, if the fish were small my mom and I would select the best fish, then string them through the gills onto a string. The smaller fish were sold whole; sailfish and marlin were cut into pieces but still put on the stringer with the the stringer passing through the skin of the individual pieces, which was thick and tough enough to hold the pieces in place. My mom would then price each piece — usually from 10-20 pesos (50 cents to a dollar) each before sending me to walk through the town calling out “isda” (“fish”!).  Selling fish this way wasn’t exactly my idea of great fun, but it was my role in the family economy and it never occurred to me to question it. Sometimes I would get lucky and people would go down to the beach when the saw the boats coming in and would buy the fish there, which was great since it meant I didn’t have to wander through the town calling out “isda”.

Selling fish this way wasn’t exactly my idea of great fun, but it was my role in the family economy and it never occurred to me to question it. Sometimes I would get lucky and people would go down to the beach when the saw the boats coming in and would buy the fish there, which was great since it meant I didn’t have to wander through the town calling out “isda”.

My Dad also brought in cash by building 4-5 “binigiw” outrigger canoes each year and selling them in Sulangan. The boats were made by cutting a twelve foot long, two foot thick tree trunk in half and hollowing it out.  This created the hull of what would become the “binigiw”. He would then — often with me helping — cut bamboo into foot-long strips half an inch wide and shaved down to about the thickness of a postcard. These strips would be woven much like a sleeping mat, and then applied to a wooden frame rising from the edges of the hollowed out log, thus forming the sides of the boat. Loreto would then collect sap from forest tries and boil it, applying it in many coats to the bamboo until a seal was created. Bamboo outriggers and a removable mast were added, and the result was a twelve foot, very narrow boat made entirely of native materials–nothing bought, everything gathered from the forest.

This created the hull of what would become the “binigiw”. He would then — often with me helping — cut bamboo into foot-long strips half an inch wide and shaved down to about the thickness of a postcard. These strips would be woven much like a sleeping mat, and then applied to a wooden frame rising from the edges of the hollowed out log, thus forming the sides of the boat. Loreto would then collect sap from forest tries and boil it, applying it in many coats to the bamboo until a seal was created. Bamboo outriggers and a removable mast were added, and the result was a twelve foot, very narrow boat made entirely of native materials–nothing bought, everything gathered from the forest.

At home we spoke our dialect — “Waray” — but in school instruction was in Tagalog, the official national language, which isn’t spoken very well in Samar. English was also taught an hour a day. From first to fourth grade, school was in Guinob-an itself–less than 10 minutes walk. There were only two rooms in the school. First and second grade were combined, and third and fourth were combined. The schoolday started at 7 and went until 5, with recess and lunch in the middle of the day. The school year began in June and continued until March.

MARTIAL LAW

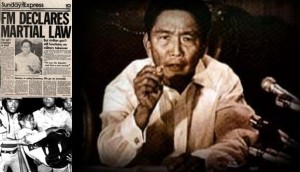

On September 21, 1972 — almost three years to the day before I was born — President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, saying this was necessary to preserve democracy and avoid a communist takeover of the Philippines. Whether or not a communist takeover was truly a threat is something I’m not any kind of an expert on. What I do know is that throughout my childhood the government was involved in an ongoing war with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and their military arm, the New People’s Army. (This is still technically going on today, although it has cooled off a lot.)

On September 21, 1972 — almost three years to the day before I was born — President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, saying this was necessary to preserve democracy and avoid a communist takeover of the Philippines. Whether or not a communist takeover was truly a threat is something I’m not any kind of an expert on. What I do know is that throughout my childhood the government was involved in an ongoing war with the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and their military arm, the New People’s Army. (This is still technically going on today, although it has cooled off a lot.)

As with the rest of my early childhood — I knew nothing other than the life in my own small town, so there was nothing to compare it to. It just “was”. I was aware from very early in my life that the military were in charge, and that there was tension whenever they came into our town. Before I knew any English to speak of I remember hearing the word “salvage”, and came to understand that in the Philippines it refers to a situation that became common during martial law where someone would simply disappear and never be found or heard from again. People would disappear either because the military made them disappear, or the communists. In provincial towns like ours the “wild west” had come to our country. I was unaware of the political context — I was just living that to me was a “normal” existence in the middle of what was an ongoing civil war.

There were many NPA insurgents in the jungle hillsides of Samar, and this meant that the the military would frequently come into our town, acting suspicious that the villagers were cooperating with the insurgents and providing support to them (which many were). In spite of the military’s efforts to control things, very frequently members of the NPA and their political partners would come into the village and hold seminar meetings in the schoolhouse. There were women among them–soldiers like the men. The insurgent team would include 5-10 guerillas, armed with automatic weapons. I was too young to fully understand what was going on in the meetings, but I understood in general that the NPA were talking about ways that they could help the townspeople with the things we needed and which the government wasn’t providing — regular clean water, medicine, health care, etc. They made sure everyone knew how what they were fighting for was righteous, and that they were moral in the way they applied “punishment” or “justice”. They also collected contributions of food and money as “taxes” although this wasn’t something that I was aware of at the time.

There were many NPA insurgents in the jungle hillsides of Samar, and this meant that the the military would frequently come into our town, acting suspicious that the villagers were cooperating with the insurgents and providing support to them (which many were). In spite of the military’s efforts to control things, very frequently members of the NPA and their political partners would come into the village and hold seminar meetings in the schoolhouse. There were women among them–soldiers like the men. The insurgent team would include 5-10 guerillas, armed with automatic weapons. I was too young to fully understand what was going on in the meetings, but I understood in general that the NPA were talking about ways that they could help the townspeople with the things we needed and which the government wasn’t providing — regular clean water, medicine, health care, etc. They made sure everyone knew how what they were fighting for was righteous, and that they were moral in the way they applied “punishment” or “justice”. They also collected contributions of food and money as “taxes” although this wasn’t something that I was aware of at the time.

When the NPA’s came to town, I would slip into the back of the room to watch their meeting beacause during the meetings they would perform beautiful patriotic songs, often with dance performances as well. During the meetings the NPA would place sentries at either end of the village to guard against surprise visits from government troops. Not all villagers would attend — but many would. To me and the others who were too young to understand the politics of it all, the main thing we knew was that the NPA were far friendlier and more helpful than the government troops, who acted like arrogant, suspicious bullies and were very frightening when they would come into the village — very different from the excitement and fun that happened wen the NPA came into town. My simple childish sympathies reflected the sense that the NPA cared about us, and were moral rather than cynical in their outlook.

THE DARK SIDE OF MARTIAL LAW–INTERROGATIONS, AND BATTLES IN GUINOB-AN

Like many towns in the deep provinces, Guinob-an developed a reputation of cooperating with the NPA, and this meant trouble for all of us. One night my father was surrounded by government troops in the middle of the night when he was outside near the house simply to go to the bathroom. They held him and questioned him aggressively until well after daylight. We could hear them shouting at him but we couldn’t do anything about it. I remember being very afraid that he might just disappear — but there was nothing we could do. They let him go soon after daylight and I remember hugging him for a very, very long time.

Like many towns in the deep provinces, Guinob-an developed a reputation of cooperating with the NPA, and this meant trouble for all of us. One night my father was surrounded by government troops in the middle of the night when he was outside near the house simply to go to the bathroom. They held him and questioned him aggressively until well after daylight. We could hear them shouting at him but we couldn’t do anything about it. I remember being very afraid that he might just disappear — but there was nothing we could do. They let him go soon after daylight and I remember hugging him for a very, very long time.

Another time they grabbed my brother Danilo, who had returned home to live in Guinb-an after having spent several years living with relatives elsewhere. He didn’t have a “cedula” (government ID) showing he belonged in Guinob-an. [[Michael comment: The use of the required “cedula” local identification document as a means of controlling the population is a practice that went back to the Spanish colonial times; in fact the term “cedula” originated with the Spanish colonizers.]] The military thought this was suspicious. They blindfolded him and strung him up so that only his toes were touching the floor, then questioned him roughly, repeatedly hitting him in the stomach and about the head with a gunbutt, trying to make him admit to being an NPA guerilla. He wouldn’t admit anything because he wasn’t an NPA. As this was going on all of us were frantic, afraid that Danilo might just disappear. My mom frantically talked to all the town officials that she knew, trying to get him the troops to relent and release my brother. Finally, by the end of the day, she got through to someone who was able to convince the military to release Donnie. Shortly after this Donnie had to leave, fleeing north to Bulacan, near Manila, where he joined another brother, Sonny, and worked as a farm hand.

Things were getting worse and worse.

Not long after the incident with Donnie, when I was 9, Guinob-an was filled with rumors that the government was planning to either burn the village or drive through the town and shoot up all the houses (these things really did happen occasionally during martial law). Afraid for their security, some families built bunkers in the middle of their house so that they would have someplace safe to retreat to in a firefight. Others began to think of evacuating. (I remember one funny thing–my Jenny and her family dove into their bunker during one exchange of gunfire, only to discover that the bunker was filled with giant Filipino fire ants. They had to choose between the bullets or the ants and they chose bullets–that’s how bad our fire ants are.)

The worst gun battle that I remember took place when I was 8….here is what I remember.

It was a normal day around 3 in the afternoon. I and her brother Rommel, who was 11, had just filled a six gallon water can with drinking water from the stream. The two of us were carrying the heavy can between us, suspended from a stick which on our shoulders, and we had just started walking home when I heard gunfire, far away at first. I stopped, told Rommel what I thought I had heard. He wasn’t convinced: “Shut up, just walk.” We walked a bit more then heard more bursts of fire, closer now, hundreds of rounds, and both us finally realized it was real and nearby. We dropped the water and ran home, but our house was empty because–as we would later learn — that my Dad had gone to his mother’s house to visit his parents in another barangay, while my Mom had gone to cousin Jenny’s house to play cards with Jenny’s mom, taking with her the two grandchildren who were living in the house at that time.

When we got to the house and found it empty — we were on the verge of panicking and had no place to turn, so we went next door to the house of my uncle (my mom’s brother), and there saw my cousin, the twenty year old stepson of my uncle crying on the floor. We asked why — he said that his parents were tending their farm and he believed that that was where the gunfire had begun. He was sure they had been killed. (The government considered anyone encountered in the jungles or mountains to be likely NPA, so tending a farm was dangerous.) He couldn’t go there because if he believed if he was found by the military alone they would kill him. He truly thought his parents were dead.

Meanwhile the gunfire was getting closer, and townspeople were running from the town in the only safe direction — the water. Donny and I joined them, diving into the water and swimming out to the deeper water, out of range (hopefully) of any bullets. In the deeper water I lost my favorite skirt — an orange one — because wearing it I couldn’t swim properly. We waited in the water for hours, surrounded by other townsfolk, as the firefight continued, then finally wound down and the gunfire stopped. While in the water,I came to understand that what had evidently happened was that military had entered the town while the NPA was there holding a seminar, and this had led to the battle. Eventually after the gunfire stopped, those in the water saw the military coming fully into the town — which we understood meant that the NPA had successfully fled into the jungle hills beyond the town. We waited until it seemed safe, then finally swam in and returned home, where we grabbed clothes and went to our grandparents house (Dad’s parents), 2 miles away.

It was pretty soon after that when my parents decided it was time for us to evacuate to someplace safer……

(to be continued ….next chapter: EVACUATION TO HOMONHON ISLAND)